My first novel, A Moon Garden, invites readers into a luminous world of war, mystery, love, and quiet revelation—where the past whispers through moonlit gardens and personal histories unfold like hidden paths. Drawing on themes of heritage, heroism, and the enduring pull of loyalty, it sets the stage for deeper explorations of history and human connection.

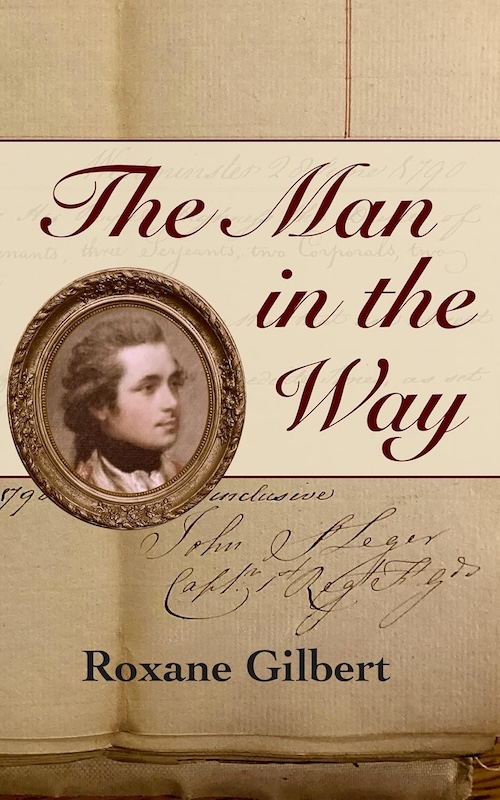

This brings me to my new book, The Man in the Way, which steps boldly into the 18th century to illuminate the life and world of Jack St Leger, a brave warrior and the confidant to future kings—whose destiny was intertwined with the great Edmund Burke.

St. Leger was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1756. Burke, the elder statesman he so admired, was born in that same city 297 years ago today, on January 12, 1729. Their shared Anglo-Irish roots, love of liberty, and dedication to public service bind them in friendship, as The Man in the Way uncovers how they navigate the tensions of politics and the risks of adhering to personal conviction in an era of revolution and change.

A Moon Garden was launched on February 15, 2020. On the 21st of February, I received a small box that contained my personal copies. You can imagine how thrilled I was to open it and gaze at the contents.

But one week after that, my excitement was off the charts, as I found my seat on a red-eye flight, then crossed a continent and an ocean. Early the next afternoon, I was checking into the Academy Hotel on Gower Street in London, a couple of blocks from the British Museum.

The research for my next book was already well underway. This was my third trip to England for the purpose of learning about the life and times of John Hayes St. Leger. However, there were still some military records at the National Archives that I had not examined. With the looming Covid shutdown, I wanted to be sure I reviewed as many of the documents as I possibly could. There was no telling when we could once again be free to travel.

I made it home in the nick of time. Pandemic restrictions were put in place 10 days later. Beginning March 16, 2020, U.S. citizens returning from the United Kingdom were subjected to a two-week quarantine.

In May, I was thumbing through a thick volume of The Correspondence of Edmund Burke. Although I knew that he was acquainted with St. Leger and that they had common interests, I was surprised to learn that they had exchanged letters. Colonel St. Leger had high-level connections, and Mr. Burke sought out the younger man for his take on the potential for a European military response to the revolution in France.

As the bond of trust strengthened between the two men, as reflected in their correspondence, Burke also solicited St. Leger’s assistance in a personal matter.

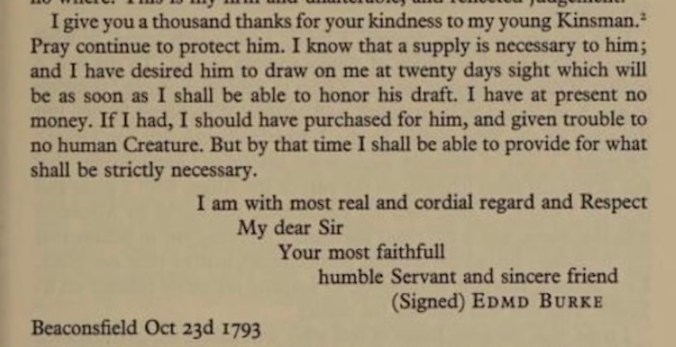

In the excerpt above, Burke is thanking St. Leger for his kindness toward his young nephew, James Nagle, a Catholic kinsman, who aspired to a military career. Under the lingering Penal Laws, a Catholic man in Ireland or Britain could not legally own firearms or hold a commission in the British Army. Colonel St. Leger helped secure Nagle’s acceptance into an Austrian Imperial Army regiment commanded by his friend and colleague Major-General Eduard (Edward) D’Alton (1737–1793), an Irish-Catholic exile. Tragically, General D’Alton perished in the ill-fated siege of Dunkirk just weeks after Nagle reported for duty.

Burke’s expression of gratitude was written in answer to a letter he had received from St. Leger, but it was not included in The Correspondence of Edmund Burke. According to the footnotes, there were a couple of letters to Burke from St. Leger that were held in an archive in Sheffield, England. I really wanted to get my hands on them.

We were two months into drastic lockdowns, and I had no clue when I could go to the U.K. again. One distinct advantage to being alive in the 21st century is that I could go online, look at the archive’s website, and send a message to find out how I could order a copy of the letters.

To my delight, I quickly received a response to my query. But unfortunately, thanks to stringent health precautions taken in England, the archive was closed. Only one or two employees were on the premises serving as caretakers, and there was no one there to fill orders.

I thanked the woman for getting back to me so promptly, cautioned her to take care of herself, and expressed my disappointment that I would not be able to inspect those documents until some uncertain time in the future. The intensity of my regret arose from my deep-seated resolve to uncover the story of St. Leger’s life. That must have come through in my message, because I got the most unexpected reply. The woman told me that she would find the letters, photograph them with her phone, and email them to me as soon as she could.

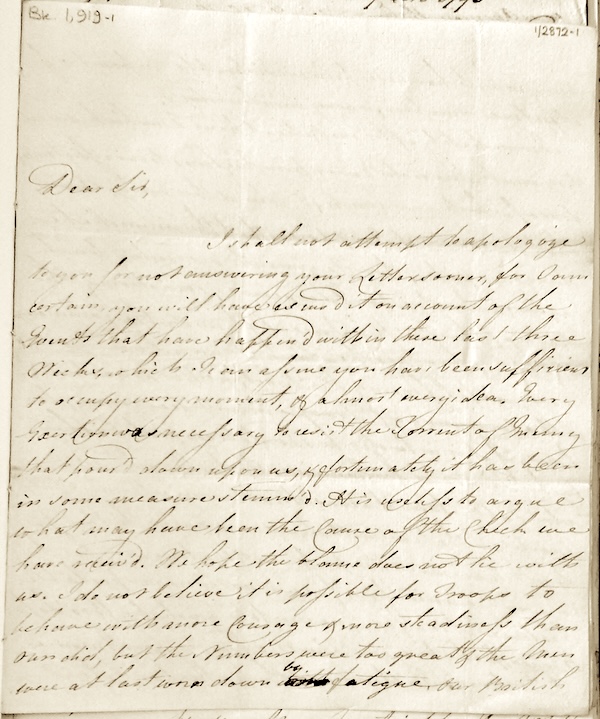

Within a couple of days, I was staring at pages of letters written in the distinctive, if somewhat enigmatic, hand of John St. Leger. It took some effort, but I was eventually able to transcribe every line.

At the time St. Leger wrote to Burke, he was the Deputy Adjutant-General to the Duke of York, fighting in the First Coalition War in Flanders. On September 8, 1793, the Duke of York ordered the retreat of the armies under his command in the battle against the French at Dunkirk. It had been a crushing defeat. The weary troops marched more than 40 miles to the southeast to Menen in the Austrian Netherlands, which became the site of further conflicts. Finally, the French withdrew and the allies found a temporary safe haven. On October 6, Colonel St. Leger took a moment to reflect on everything that had transpired. This is how he began his somber letter to Edmund Burke:

Dear Sir,

I shall not attempt to apologize to you for not answering your letter, for I am certain you will have excus’d it on account of the Events that have happen’d within these last three weeks, which I can assure you have been sufficient to occupy every moment, & almost every idea. Every exertion was necessary to resist the torrent of misery that poured down upon us, & fortunately it has been in some measure stemm’d. It is useless to argue what may have been the Cause of the Check we have receiv’d. We hope the blame does not lie with us. I do not believe it is possible for Troops to behave with more Courage & more steadiness than ours did, but the Numbers were too great & the Men were at last worn down by fatigue. Our British Army which has never been considerable in point of effective numbers, is very much reduced.

My feelings about St. Leger evolved, as I uncovered the long-hidden truth about him. These glimpses—Burke’s gratitude for aid to his nephew, St. Leger’s sober battlefield reflections, and the trust placed in him by one of history’s greatest defenders of liberty—reveal a figure of substance and character. Far from the hedonistic dismissal of later historians, John Hayes St. Leger emerges as a patriot, friend, and man of quiet decency whose story deserves to be told anew.

And the more I learned about the dignity, moral principles, and unabating patriotism of Edmund Burke, a man St. Leger deeply admired, I found I shared his view.

Edmund Burke entered public service in 1765 as the private secretary to Prime Minister Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham. They remained friends until Lord Rockingham’s death in 1782. In December 1765, Burke was elected to the House of Commons.

To this day, Burke is revered as a political philosopher. He was at the vanguard of classical liberalism and laid the foundation for modern conservatism. Despite his achievements, he died heartbroken.

When Burke retired from Parliament in June of 1794, he believed that his legacy would be carried on by his son Richard. But the young man died of tuberculosis on August 2, 1794, at age 36, one week after winning the election.

A second great disappointment that Burke endured was his failure to convince his fellow legislators of the excesses and abuses of the East India Company, and the need to constrain its power. In August of 1796, Jack St. Leger had boarded a ship to embark on the long and perilous journey to Calcutta, to serve on the general staff of His Majesty King George III under the auspices of the East India Company.

Edmund Burke died in Beaconsfield, England, on July 9, 1797. One month later, Jack was headed for Manila as second-in-command of an expedition to confront the Spanish rivals of the East India Company. But as the flotilla was crossing the Bengal Sea, political tides turned. When St. Leger’s ship docked in Malaysia, he received word that the Holy Roman Emperor had signed a peace treaty with France. This dramatic shift in alliances caused an instant change in priorities. Edmund Burke’s dire warnings of the destructive nature of the unchecked oligopoly in South Asia would play out catastrophically in the years immediately following his death.

The Man in the Way by Roxane Gilbert will be released through Amazon on January 23, 2026. The ebook is available for pre-order.

Please consider supporting this site by using my links to Amazon. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you!

Discover more from Roxane Gilbert

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.