Something happened during my 17th summer that was not on my bingo card. I already knew better than to trust my mother’s judgment, but I wasn’t yet even dimly cognizant of how much growing up I needed to do, before I could safely rely upon my own.

I had been away since I graduated from high school in June. It was after Labor Day when I returned home. Mother was fired up. As we bumped along in the VW Beetle on the 25-mile drive from the airport to our house, she eagerly told me that she had gotten sober and was in a recovery program. That’s where she met John, a bohemian poet. I would get a chance to meet him on Friday.

It was about seven o’clock when John pulled his jalopy into our driveway. Despite the unimpressive car, I was pleasantly surprised by his looks. Tall and lean but not skinny, he looked to be in his fifties. He had shaggy dark hair, a high forehead, and a short, scruffy beard. The pockmarks on his face didn’t detract from his appearance.

Instead of sitting on the sofa, John strode to the center of the living room and sat on the white tile floor. To my astonishment, Mother sat next to him, her legs crossed Indian-style. She indicated a spot in front of her and invited me to join them.

“Have you ever tried pot?” she asked.

“No!” I sputtered.

“Well, my friend Charlie is a cop. He told me that it would be best for you to try it at home, before you get exposed to it at college.”

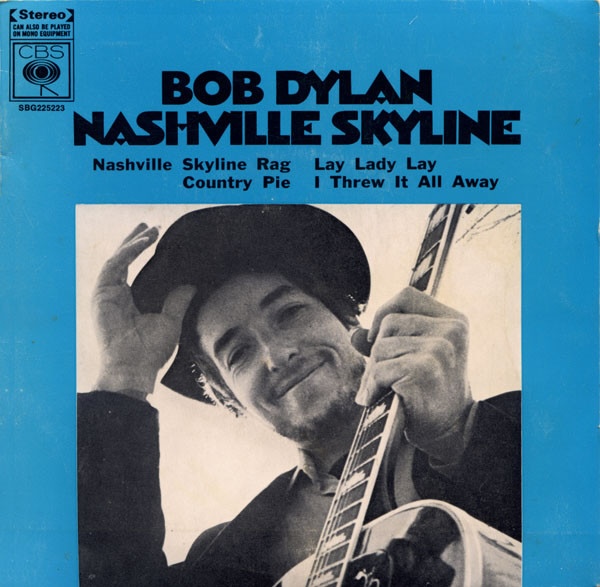

I was intrigued but aghast at how the evening transpired from that moment. Mother and John got a little weird, laughing at nothing in particular and swatting at invisible fireflies. Things mellowed out, as we listened to Nashville Skyline by Bob Dylan. But it came to a screeching halt after the first side ended and John flipped the record over.

As soon as “Lay Lady Lay” began to play, Mother ordered me to my room and told me to lock the door.

“Why?” I asked.

“Just do as I say,” she insisted.

Pouting, I rose to my feet. Mother followed me into the hall, where she quietly confessed that she did not trust John. Genuine shame mingled with the look of sorrow on her face.

Maybe she was worried over nothing, but it was also possible she knew something I didn’t. In any case, I felt like I had been sucker punched. Fighting back tears, I wished with all my heart that I could get on a plane and wake up the next morning somewhere sane.

My mother, may she rest in peace, could be oddly naive. Moreover, she often failed to exercise common sense. Whatever rationale she had for taking Charlie’s misguided advice, it was not grounded in good judgment. All I know is that Mother believed she was clever.

I never thought of cleverness as a negative trait, until I met abstract painter and printmaker Sam Tchakalian (1929-2004). In the late 1980’s, when I worked at a fine arts press in the San Francisco Bay Area, I was privileged to assist him in producing some of his monotypes. Although the style of his paintings and prints didn’t hold any special appeal for me, I was impressed by Sam’s straightforward approach to creative expression.

I’ll never forget when Sam said, “I hate clever art.” The remark came out of nowhere, as he was looking at an inked plate, trying to decide if it was ready to print. As I thought about what he said, I realized that I felt the same way.

Sam’s process for making art was nothing, if not direct. Watching him squeegee a thick rectangle of mat board, loaded with ink, over a printing plate fascinated me. He would stop to load another board with a different color, then drag it in the opposite direction, going back and forth until the plate was coated. After he finished scraping, blending, and wiping, I would retrieve a large sheet of paper from the soaking tray and blot it until the moisture no longer glistened on the surface. Grasping the paper by its diagonal corners, I lifted it up and laid it over the inked plate. After covering the paper with thick felt blankets, I slowly turned the press crank to glide the bed under the heavy roller. Once it came to a stop at the other side, I peeled back the blankets, raised the paper from the plate, and carried it to the drying rack.

The best part was when the prints were dry, and Sam would come back to the studio to review his work. We stood together next to the long, wide table, examining the prints, trying to determine which ones to keep and which ones to toss. Of course, most of them passed muster.

Sometimes I kept Sam company, while he signed the bottom righthand corner of each piece in the stack. It was fine if we didn’t say anything, but if he felt like talking, I enjoyed listening. Now I wish I had asked him more questions. One day, he told me that his father had fled the slaughter of Armenians by the Ottomans during the genocide of the early 1900’s. He ended up in Shanghai. That’s where Sam was born. In 1947, as the communists were consolidating their takeover of China, he emigrated with his mother and two brothers to San Francisco. I’m sure he had quite a tale to tell.

Discover more from Roxane Gilbert

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You are compiling quite a resume of life young lady! Do you have any thought or plans of a “This is my life” project? (The Book of Roxane).

Wouldn’t you know it, I do have an unpublished memoir stored away in my computer. But it doesn’t address all of my experiences. Maybe someday I’ll compile a few more stories from my life!