What is a legacy? If you look to the dictionary for an answer, the first definition that pops up is money or property left to someone in a will. The second definition is somewhat abstract, but it is the more interesting one. A legacy is something we inherit from a predecessor. In this second scenario, that amorphous something left to us may take many forms. It could be moral values, philosophical teachings, scientific discoveries, military victories, peace treaties, awe-inspiring architecture.

Many of us hope our legacies will be reflected in how we raise our children. Perhaps our spirits will live on in the hearts of generations that are yet to be born.

A wealthy man I knew endowed a business school at a university in California. It now bears his name. Another wealthy acquaintance has a music school named for her at a Midwestern college. They leveraged their vast financial resources to influence how they would be remembered, while benefiting institutions they valued.

The artists I have known who have achieved the most recognition and success are highly driven to be creatively productive. Many of them never had children, whether or not they were married. If they are motivated at all by their future legacy, it is fair to speculate that they expect it to be manifested through the body of work they leave behind.

I used to joke that I was already a footnote in art history, thanks to the work I did as a printer’s assistant at a fine arts press near San Francisco. Years ago, when I met the curator for the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, I was amazed that she actually knew who I was. She had seen my name on the documentation for many of the lithographs in their collection.

Now that I channel my creative energy into writing, I am striving to make an impression in a new arena. It surprised me to learn that, in his last days, Alexandre Dumas père (1802–1870), the author of so many popular historical adventure novels, was feeling uneasy about his legacy.

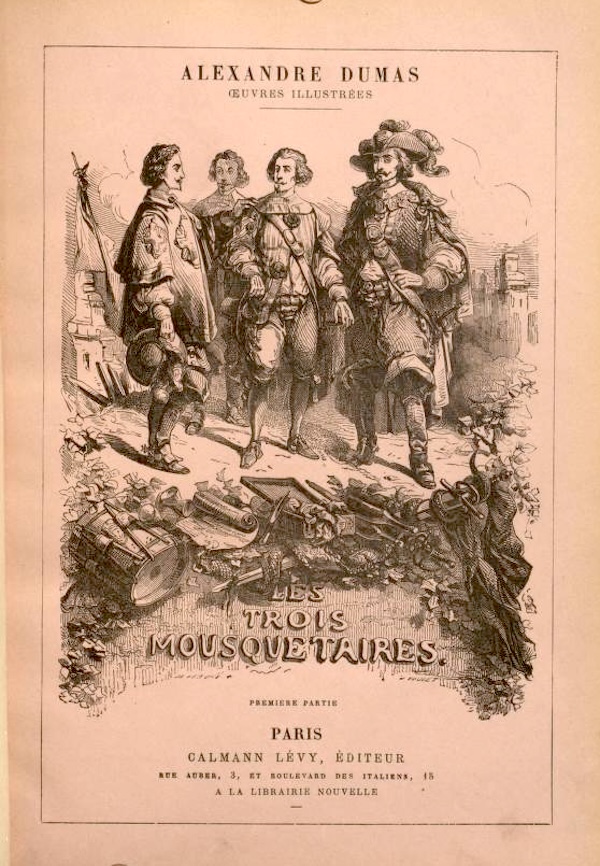

The Three Musketeers by Dumas père had originally been published in 1844. A posthumous reissue of this masterpiece included an introductory letter written to the late author by his son, Alexandre Dumas fils (1824-1895).

He begins the letter with these words:

MY DEAR FATHER: In the world to which you have gone, does memory survive and retain a recollection of things here below? or does a second and eternal life exist only in our imagination, engendered, amid our recriminations against life, by the horror of annihilation? Does death utterly annihilate those it snatches from us, and is memory vouchsafed only to those who remain on earth? Or is it true that the bond of love which has united two souls in this world is an indestructible tie, not to be severed, even by death?

Worn out by work, Dumas père had been staying with his son at his house near the coastal village of Dieppe since August 1870. On the morning of December 4, Dumas père was too exhausted to get out of bed. His son relates the poignant conversation that would be one of their last:

He fixed his great kindly eyes on me, and in the tone of a child beseeching its mother, he said to me:

“I entreat you do not force me to get up, I am so comfortable here.”

I did not insist, but sat down on his bed. Suddenly, a strange wistfulness took possession of him, and a solemn and melancholy expression settled on his face; and in his eyes, so caressing the moment before, I saw tears gather. On my inquiring the cause of his sadness, he took my hand, and, looking me straight in the face, said, in a firm voice:

“I will tell you, if you promise to answer my question, not with the partiality of a son, or the indulgence of a friend, but with the frankness of a valiant companion in arms, and the authority of a competent judge.”

“I promise to do so,” I replied.

“Swear,” he said.

“I swear,” I again replied.

“Well then”—he hesitated for an instant, then making up his mind— “Well! do you believe,” he said, “that anything I have written will survive me?”

And his eyes watched me eagerly.

“If that is your only anxiety,” I replied gaily, “you may rest in peace; much indeed will survive you.”

“Is that true?” he asked.

“Certainly,” I replied.

“On your honour?” he said.

“On my honour!” I repeated.

And as I cheerfully smiled to hide my increasing emotion, he was reassured and believed me. Then he drew me toward him, and folded me in his arms. After that he spoke no more, as though nothing interested him any longer here below.

The next night at 10:00, Dumas père quietly passed away. In the ensuing years, Alexandre Dumas fils took note that his father’s books sold millions of copies, in multiple languages.

One hundred fifty-five years after the death of one of the greatest storytellers ever to live, the timeless novels by Alexandre Dumas père are still in print.

Discover more from Roxane Gilbert

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: The Legacy Continues | Roxane Gilbert