After I finished writing the manuscript for my first novel, A Moon Garden, I found myself in the unaccustomed state of having free time. One morning, I sat down at the computer and did a web search, to see if I could find a portrait of an aristocratic British soldier from the 1780’s, who looked how I had imagined the hero of my book. To my surprise and delight, I did. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much information online about the handsome young colonel, and most of what I uncovered was titillating gossip and hearsay masquerading as facts.

When I wasn’t at my eight-to-five job, I wrote query letters to literary agents, explored the option of self-publishing, and outlined the plot of my next work of historical fiction. It was set in the late 19th century, with the action taking place in Manhattan, Paris, and London. After reading up on what everyday life was like during that period, I traveled to those cities and walked around the neighborhoods where the narrative would unfold.

My literary plans abruptly changed in London. On my last day in town, I went to see the portrait of the British Army officer who resembled A Moon Garden’s hero. As soon as I saw it, I knew I had to write about the man in the painting. His forgotten story needed to be told.

Over the course of the next three years, I rummaged through libraries and archives, pouring through rare books, old newspapers, and public records, constructing a timeline of an extraordinary life and a turbulent world.

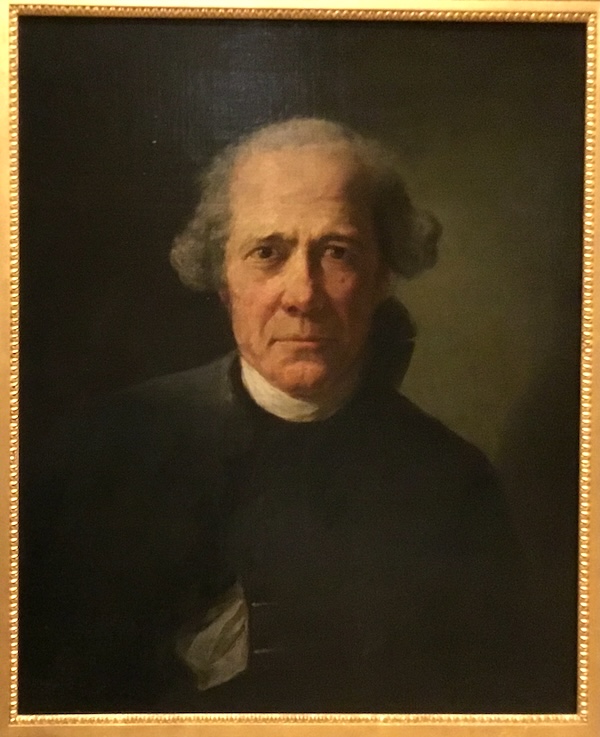

About a month after the publication of A Moon Garden, I went to the National Gallery in London. A lot of paintings in this collection depict historical figures whose lives have been well documented. But there were some nameless faces among them that piqued my curiosity. In particular, there was a 1791 painting attributed to a French artist named Joseph Ducreux (1735-1802). It was simply titled Portrait of a Man.

It caught my eye, because the man had an uncanny resemblance to an old friend of mine. Even their hairstyles were the same. After familiarizing myself with other paintings by Ducreux, I became more curious. Portrait of a Man barely fit within Ducreux’s oeuvre. Although he was an artist at the Court of Louis XVI and painted traditional portraits of the King and Queen of France, as well as members of the French noble class, he was also known to push the limits in capturing odd facial expressions. His self-portrait from c.1783 is a prime example of this.

Portrait of a Man is a little quirky, but not remarkably so. Perhaps the man’s eyes look a bit sad and bewildered, but his face is not nearly as contorted or eccentric as some of Ducreux’s other renderings. His humble attire leads me to assume that this was not a commissioned work. So what motivated the artist to create this painting? Does it depict a friend? Or was this a stranger whose face was so captivating that the artist felt compelled to paint him?

Increasingly, since I had resolved to find out all I could about the all-but-forgotten British Army officer who resembles my fictional hero, I look beyond the artistic merits of a painted portrait. I want to learn what I can about the person on the canvas, who is staring out from the past into the distance.

A couple of days ago, I came across some paintings by Michelangelo Pittatore (1825-1903), an artist from Asti, Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (now Italy). Pittatore worked for a while in Rome, where he met Rudolf Lehmann (1819-1905), a Jewish artist from Ottensen, Duchy of Holstein, German Confederation. The two artists became life-long friends. Lehmann moved to London in 1866 and became a British citizen. Pittatore moved to London a couple of years later, then returned to Italy in 1872.

In 1863, Pittatore painted a portrait of Elia Moise Clava (1808–1868). A resident of the artist’s home town of Asti, Mr. Clava was a philanthropist and a prominent member of the Jewish community.

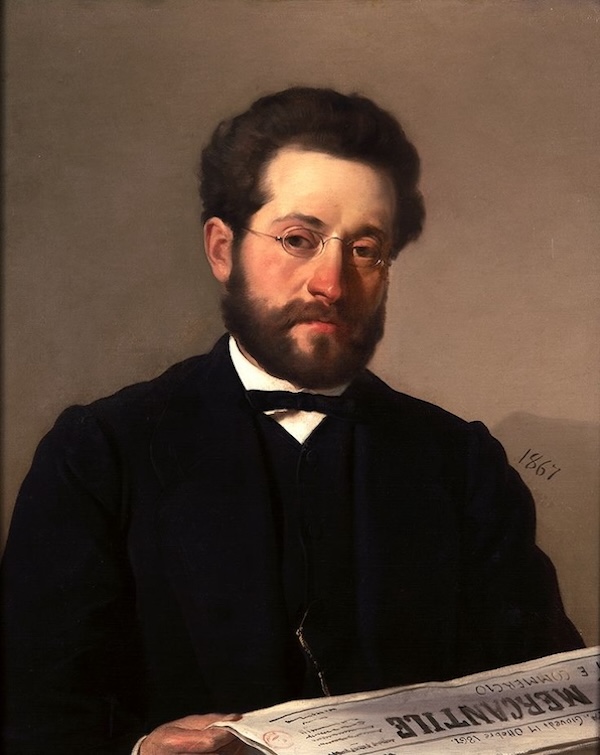

Five years later, Pittatore painted a portrait of Raffaele Debenedetti (1828-1889).

A quick internet search revealed nothing about who Debenedetti was. Eventually I found some answers. It turns out that he was also a prominent member of Asti’s Jewish community, and he was married to Mr. Clava’s daughter, Marianna (1832-1904).

There was a Jewish presence in Asti at least as far back as the 14th century. However, they were expelled in 1530 by Beatrice of Portugal, Duchess of Savoy. After her death in 1538, they were readmitted.

The Jewish Ghetto in Asti was established in 1723. From 1730-1798, Jews of Asti, mostly merchants and bankers, were forced to live in it. By the time Elia Moise Clava and Raffaele Debenedetti were born in the early 1800’s, it was legal for Jews to live outside the ghetto. Both men were still alive in 1861, when legal equality was granted to the Jews of Italy.

When Pittatore painted these portraits, there were probably between 200 and 300 Jews living in Asti. There are no precise population records available, but by 1938, when Fascist racial laws were enacted in Italy, Asti had perhaps 30,000-50,000 residents, of whom 100-200 were Jews. No doubt, some of them fled. Approximately 100 remained, and 51 of them were slain during the Holocaust.

Part of the Nazi playbook was the destruction of Jewish records. One motive for this was the erasure of evidence of their heinous crimes, but there was a more insidious reason. They wanted to wipe out the identities, the achievements, the legacy, and the continuity of the existence of the Jewish people.

There were also some evil men who sought to destroy the life and reputation of the British Army officer who inspired me to write. They were unceasing in their efforts, even after his death. To this day, the patriotic soldier’s reputation is a shambles.

The trail of Raffaele Debenedetti’s life quickly goes cold. A cryptic message on an Italian website provides the likely reason for this. It describes the Debenedettis as “one of the families who, after a long and deep stay in Asti, suffered the Nazi-Fascist persecution.”

It is up to us to remember. May they never be forgotten.

Discover more from Roxane Gilbert

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another patient, dogged, determined, detective destination…the government should have you finding the lost anything!