Years ago, my experience as the senior designer at a theme-party production company led to a contract with an architectural firm that was developing a multimillion dollar resort for a client in Japan. It was up to me to direct a team in planning the function and decor of the interior common spaces, including everything from seating areas to bathroom fixtures, to garbage cans and ceiling fans, to uniforms worn by the staff. Given my personal expertise, I also had the task of conceptualizing and developing daily special events for the entire calendar year, that would take place outdoors in the plaza.

The most interesting aspect of the project, however, was a component that was completely new to me: experiential scripting. We mapped out what the guests would see, hear, feel, taste, and even what aroma they would smell, from the moment they set foot onto the property. It was up to us to make it fun, surprising, and memorable. Attention to detail was essential.

One day, the creative director took me and the other two team leaders on a field trip to San Francisco. As we walked along a street in the vicinity of Union Square, he suddenly stopped in front of a boutique and gestured toward the entryway. “What do you see?” he challenged.

Although I had walked along this street on many occasions, it was the first time that the dull-red, glazed square tiles framing the display window had ever pierced my awareness. Somehow, I had never before noticed the small octagonal black, white, and green tiles at my feet. The patinated bronze lantern dangling from a domed overhang over the mahogany-trimmed, beveled-glass door had not caught my eye until that instant. We walked up Powell Street towards Chinatown, consciously soaking in the architectural elements that contributed to the distinct charm of this neighborhood. That day forever changed the way that I experience my surroundings. As time has passed, I am increasingly conscious of the ways that my environment affects me.

Walking is one of my daily pleasures, and London is one of my favorite places to indulge this habit. I went there at the end of February 2020, to tie up some lose ends in the research for my latest historical novel. With COVID lockdowns looming and the prevailing uncertainty as to how long they would last, I wanted to be sure I had a chance to see some military records at the National Archives. Despite the winter rains, cold weather, and the amount of time I spent in reading rooms, I was surprised to see on my iPhone Health app, that I walked a minimum of three miles a day on this trip. On those days when I explored the places that the hero of my book had visited in the late 1700’s, I walked anywhere from six to nine miles.

It’s not that I didn’t get tired. Some days I had to push through shoulder or back pain to keep going. But the invigoration of walking through central London or along the River Thames outweighed the strain.

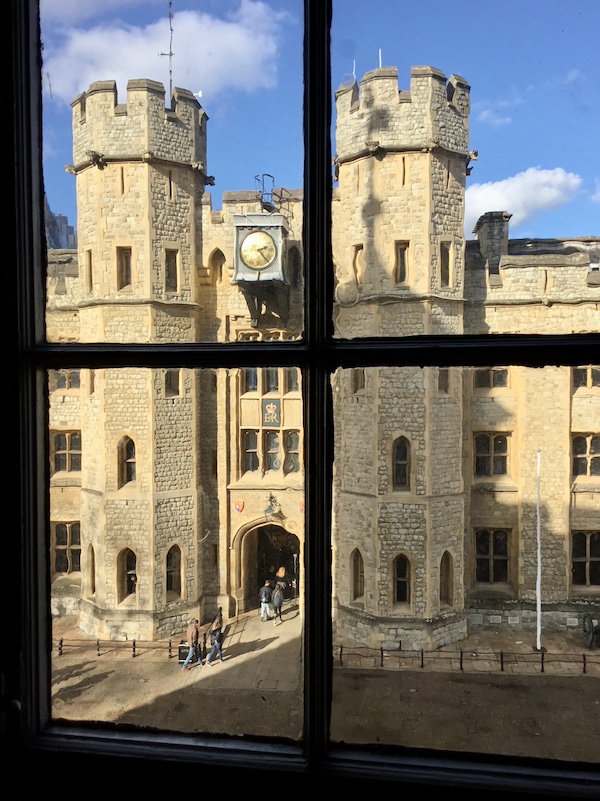

When I stand amidst buildings that were constructed hundreds of years ago, I can find something to discover in each brick, stone, or paver. Every garden path leads to a sense of wonder.

Back in the USA, in the neighborhood where I live, walking a couple of blocks to the local park, circling around it, and returning home can feel like a chore. The park itself is merely a well-maintained massive lawn with a few trees and benches at the perimeter, At one end, some concrete walkways converge at a children’s play area. It looks like it was inspired by SpongeBob SquarePants and constructed with giant Tinkertoys and Lego sets. The surrounding houses are pretty enough, but they are all overbuilt for the size of their lots. As in most American bedroom communities, the biggest, boldest feature of each dwelling place is the garage door.

Despite the fact that every house has a two- or three-car garage, most of the residents park their cars and pickup trucks in their driveways or on the street. As the neighbors prosper, many of them cut down the beautiful ornamental trees in their front yards and pour a concrete slab, where they park their oversized recreational vehicles.

Perhaps it is not so ironic that I feel more connected to the buildings in England’s cities than I do to the houses in my own community.

When I was 18-years old, I dropped out of college and went to New York. It was a dangerous place, and you had to keep your wits about you to avoid trouble. Being on the street was generally safer than riding the subway, however, and walking from place to place became my favorite mode of transportation. The technology of the day didn’t enable watches or phones to track our steps, but it was not unusual for me to log several miles a day.

At the urging of my uncle, I enrolled in a class at the Art Students League. My teacher was an older society lady with white hair and a sterling silver nutcracker, that she used to loosen the stuck caps on tubes of oil paint. I learned a lot from her about color and chemistry, but more importantly, she taught me what it meant to see.

The world back then was chaotic. To a teenager, it was particularly fraught with uncertainty. Some of my men friends were fighting in the war in Vietnam. Others were trying to figure out how to evade the draft. In this era of rage and fear, a talented folk singer and composer named Phil Ochs achieved prominence, then crashed and burned from a combination of angst, alcoholism, and mental illness.

I had been impressed by Mr. Ochs, as he was rising in his career, and there was something that he wrote in the liner notes of his album, “Pleasures of the Harbor,” that moved me deeply. In fact, during my brief first stint at college, I had copied it out onto a piece of paper, using magic markers and my best penmanship, and taped it to the wall of my dorm room. After all of these years, it has come back to me:

“Ah but in such an ugly time the true protest is beauty.”

Answers may elude us, but perhaps those words can help to shape the next step in our journey.

Discover more from Roxane Gilbert

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.